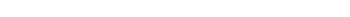

honoring

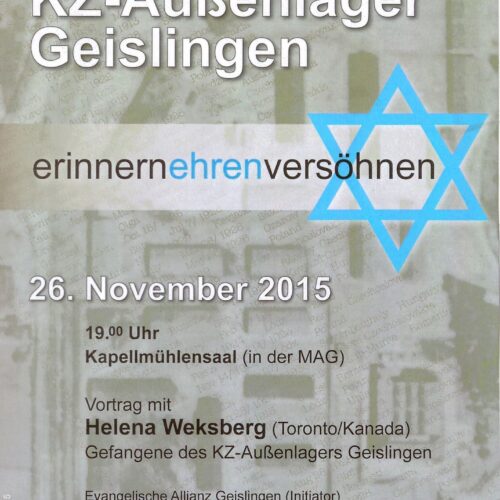

Sie haben Schreckliches erlebt, die Shoah überlebt und sind 70 Jahre später nach Geislingen zurück gekommen - wunderbare Menschen.Lenka Lebovics, married Weksberg

My name is Helena Lenka Weksberg, maiden name Lebovic. I am a Holocaust Survivor of the Ghetto Mateszalka, Hungary, concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, Geislingen, and Alach near Dachau. In those days, I faced death everyday of my life and with the grace of G-d or by any other circumstances, I survived. Returning to the places where I spent the darkest days, I have now decided to let my memory speak.

Lenka Weksberg died on March 10, 2023 in Toronto at the age of 96.

My story begins in Teresva, in the Carpathian Mountains. I come from a family of 6 children, 5 girls and one boy, Helen, Charlotte, Lenka, Theresa, Rosalie, my late brother William, and my parents, Israel and Regina. We were a very closely knit family and enjoyed a normal life. The happy years ended in 1938 by the Munich conference when Germany gained a western slice of Czechoslovakia and then subsequently engulfed the country. In 1942 Ukrainians occupied our territory. I went to Ukrainian schools. A few months later Hungary occupied our territory. Hungary and Germany were allies and the same laws against the Jews applied as in Germany. In 1944 Germany occupied our territory.

Days and nights, cargo trains were bringing little Jewish children, old people and people of all ages, packed like animals going to the slaughter houses direct to the crematoriums.

These cargo trains came from all over Europe – Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Hungary, Germany and other European countries. What happened in the third Reich is beyond one’s power of imagination. The incomprehensible remains incomprehensible. How can I speak about the unspeakable tragedies? But I will speak for those who are silenced forever.

In 1942 we were taken to the Mateszalka ghetto in Hungary. In 1944 we were transported by cargo train to the death camps in Nazi-occupied Poland in Auschwitz- Birkenau. When we got off the cattle car we were place in a long line facing the S.S. officer Dr. Joseph Mengele. As each prisoner took their turn in front of him he decided if you lived or died. If he pointed to the right – you lived. If he pointed to the left – you went to the showers to be killed by Zyklon B gas, after which your body was burnt in the crematorium. My mother was sent to the left to die. My sister Rosalie aged 12 was also sent to the showers, but somehow she ran to the right side with the other sisters, narrowly escaping death.

After the selection process, we were shaved by the male inmates until no hair was left on our entire bodies. With our shaved heads, we hardly recognized each other. We were normal-looking human beings just a little while ago but it hardly seemed to matter anymore. We had nothing left. All we possessed was our naked existence and our memories of the past. They stripped us of everything. We were deprived of our clothes, our names, and our identity. My name was 20,633. I will never forget the first night in Birkenau, which was the last time our family was alive together. Friends and relatives, including my mother and my brother walked to their death without saying goodbye. They were so brave, so innocent. That night the heavens wept. We were placed in a block of 1,500 people. Capos were prisoners themselves that worked for the Nazi guards, helping to carry out their orders and control the rest of the prisoners. As we were told to line up towards the barracks, the Capos were screaming, “You better be quiet! Your parents, your brothers and sisters are burning right now.” Our only light at night was the light from the crematoriums where our families were burning.

The Capos were wicked beasts cursing and kicking the inmates. They were vicious sadists who enjoyed inflicting pain on the prisoners, telling us we would be free when we would go through the chimney. However, as in all groups, there were always some exceptions. One Capo, Laura, always comforted us. She said “sometime wonders can happen, and you will be free. Tell the world what is happening here.” But the world did know. The world did nothing as we were being slaughtered. Every day, twice a day, at designated times; we had to stand in line, in rows of five. These head counts were called “roll calls”. Naked, we were stood in line, in the rain, in the cold, and in the heat. We were counted by the S.S. guards with their dogs. We had no running water. Five hundred people had to use the latrine at the same time for a few minutes while being controlled by whips. Some people wanted to commit suicide. Some intentionally stepped out of line, and others did not come out of the barracks. Punishment for these actions was immediate death. Others killed themselves by touching the electric barbed-wired fence. I watched a 16-year old girl touch the electric fence, it was the most horrible death I witnessed.

The worst was to listen to the unbelievably beautiful music played by the Auschwitz-Birkenau orchestra with lively music, while the cattle cars continued to arrive from all over Europe with their families. Many thought they were there for a holiday but meanwhile, they were led out of the train and immediately executed. The humiliation, the starvation, the beatings, the head counts, so much crying without a single tear, so many endings, a massacre without a reason. Who has the right to extinguish a culture? And the worst of all was standing in line, most of the time naked, with the question “when will my life end ?” After 3 months, we were lucky to get out of Birkenau. We were among the eight hundred prisoners requested by the Wurttembergische Metallwarenfabrik to work in the factory in Geislingen. We learned later that, days before we arrived in Geislingen, the inhabitants were warned on the radio and newspapers that eight hundred political prisoners who wanted to break up the country were coming to the city to work as slave labourers.

Conditions in Geislingen were different from conditions in Birkenau. It was not a direct route to extermination. However, even though we didn’t have the gas chambers and the crematoriums, it didn’t stop the S.S. from taking the sick to Auschwitz. There too, in Geislingen, we were hungry and cold. Many people searched through the garbage cans for food. During our daily walk to the factory, sometimes German women from the town would throw an apple or two between the lines for the prisoners. The guards warned us, “If you pick up those apples, you will be shot immediately.” Nobody dared to pick them up. There were some righteous gentiles who cared and sacrificed their lives and their freedom. One of them was the foreman of the factory, Adolph Schoofs, who put his life on line to help us. He was a man of grace. Sometimes he brought us a piece of bread. He risked his life to do this for us. One day….. We were transported by cattle car and arrived in Alach, near Dachau…. When we arrived in the concentration camp we saw piles and piles of human bodies, skin covered skeletons, dead from starvation. They were lifted up by a bulldozer as if they were garbage, and put onto trucks to be taken away.

What happened to humanity ?

We slept on the ground, it was freezing. The only warmth we had was from sleeping close to one another. The next day, we had to line up. We were going on a death march. We were only eight hundred half-starved women in this group, and we had a whole contingent of heavily armed S.S. accompanied by dogs. We walked for miles until we came to a forest. At the age of 18 why I have to die? In the middle of the woods forest, there was a train with cattle cars. We were told to go up a little hill to get to these cattle cars. Nearby I saw a group of male prisoners struggling to go up this little hill. The guards did not give them enough time and shot them. Fortunately we were able to climb up the hill and reach the cattle car. After loading onto the train we travelled for three days without food or water. The train went back and forth, without any destination. On the third day, April 30, 1945 we heard artillery fire. I thought they were shooting prisoners. My heart started to pound. Suddenly the train stopped. When the doors opened we were liberated by the American Army in the forest of Staltach. The black clouds of fascism came to an end. We were free.

I did not celebrate my freedom at that time because it was painful and very disturbing to be free. I forgot what freedom was. What shall I do with my freedom? Where shall I go? I knew my mother and my brother were not coming home. We had no clothes, no identity documents. The Red Cross put us in a military barrack. When I ate my first piece of bread, I developed extreme abdominal pain and fell to the ground. I became completely blind. I couldn’t see anything. I could only hear the sounds of the waves of the ocean. I was dying. Hundreds of people died eating their first piece of bread after the war. I was taken to the hospital. Fortunately after a few days and I improved and could see again. Going back home, I had nothing from the past, everything was gone, all my possessions were gone. There was no reason for any of us to stay at our home. There had been so many Jewish people in this town but no one was left. The territory was now under Russian rule.

I decided to go back to Czechoslovakia, but the Russians did not allow this. I had to sneak through the Romanian border. Since I did not have any documents the Romanian police took me to prison. I stayed there for a few days. After the police realized I was holocaust survivor they let me go. I lived in Prague for one year. Every single day, I visited my father who had tuberculosis and was in a sanatorium. I had water, bread and sugar, and that’s what I ate for almost one year. I was a free person and I was happy. My sisters and I went to the United States and to Canada. We married, and had children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. I have a son and a daughter, five grandchildren and three great grandchildren. My son is a dermatologist, and has a successful private practice in Toronto. My daughter is a geneticist and researcher at the Hospital of Sick Children, a world famous pediatric hospital in Toronto. I am grateful for Wurttembergische Metallwarenfabrik for asking 800 prisoners to work in the factory. Otherwise, we would have had to face death in Birkenau. Returning to Geislingen, I walk with a name, not a number. Now I walk as a proud Jew. I walk with pride as a citizen of Israel, and as a proud citizen of Canada.

My most important message……

Although we cannot change the past, we can influence the future to live in harmony and peace.

Thank you again for your presence.

Lenka Weksberg